by Ian Coutts

“You know the movie The Matrix? It’s essentially like that.”

Major Giuseppe Ramacieri is trying to explain the thinking behind the Army’s proposed Land Vehicle Combat Training System (LVCTS).

If the Keanu Reeves movie of life inside a computer-generated virtual world seems a tad far-fetched, the analogy seems less so when Ramacieri, project director within the Directorate of Land Requirements tasked with steering the LVCTS through its early stages, talks about the project in depth.

Someday in the not too distant future, Leopard, TAPV and LAV crews will be able to train on simulators that will look, feel and behave just like the real thing – “real radios, real hand controls.” And they will be able to operate the vehicles in a variety of different terrains – desert, forest or whatever else is needed. They will even be able to engage an enemy force. All virtually.

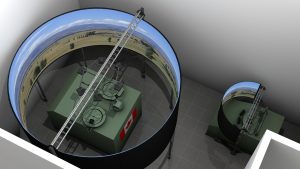

And someday it may even be possible for crews scattered across Canada to train together in a common simulated environment.

For crews – commanders, gunners, drivers, and others – there is no substitute for training on real vehicles in the field. But it’s expensive in terms of fuel and wear and tear on the vehicles, especially with an inexperienced crew. Simulation can help, by preparing the crews so that when they do get into a real vehicle or they are operating a light armoured vehicle (LAV) or Leopard tank as part of a larger formation, they already have a fairly good idea of what to do.

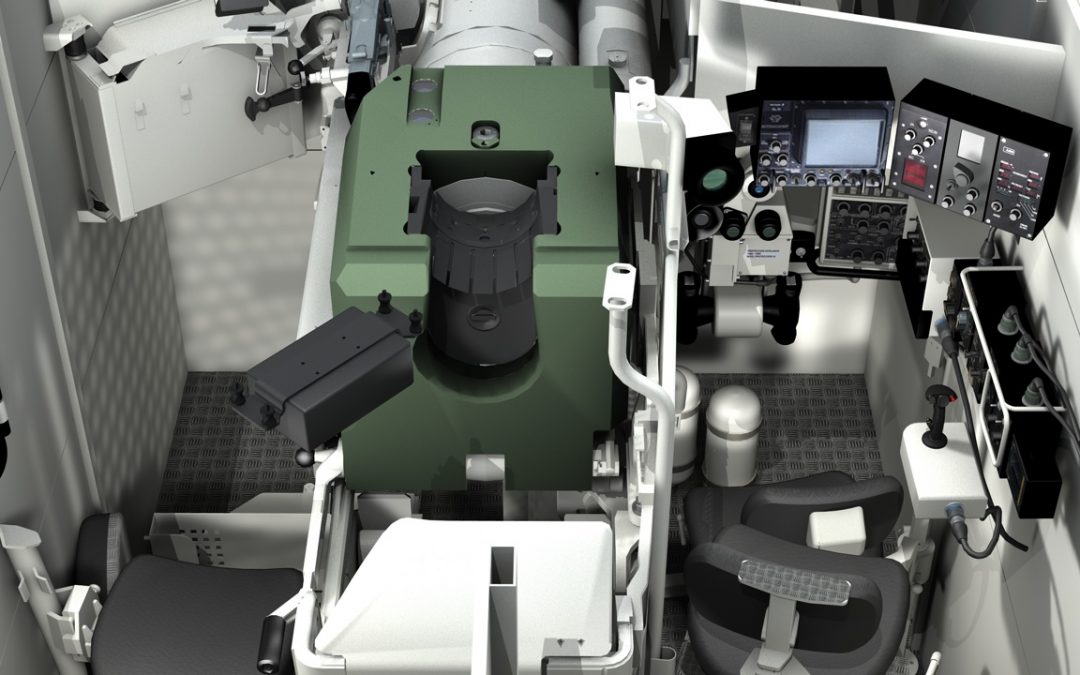

LVCTS Leopard 2 tank simulator

That’s the goal behind the Land Vehicle Combat Training System. It’s an ambitious – and potentially very expensive – undertaking. One centre would be a challenge; the Army is talking about creating five separate locations for its planned simulators across Canada – Gagetown, Valcartier, Petawawa, Shilo and Edmonton – to allow crews to train locally.

“This is one of the largest simulation projects for land vehicles in the world,” said Ramacieri.

The simulators will provide for a full range of training – soldiers will be taught to drive the Leopard 2 and LAV 6.0 via a simulator with a full range of motion, and crews will be able to learn how to function together – or as part of a larger formation.

Each centre will have enough simulators to provide training for “up to a square combat team” – a tank squadron and a company of infantry, said Ramacieri. As well as the high-fidelity simulators that replicate the interiors and behaviour of the real-life combat vehicles, to be used for driver and gunnery training, the centres will also feature medium and low fidelity systems. The medium-fidelity systems will be used for tactical training.

“They might have real hand controls,” he said, “but everything else will be on touch screens.” Low-fidelity systems would do without even hand controls and will be used for “support training. For example, simulating aircraft, friendly forces and so on.”

The gestation of the LVCTS has been a drawn-out one, even by the sometimes-glacial standards of Canadian military procurement. “The project started in 2008,” Ramacieri acknowledged, “but only for the LAV 6.0, which hadn’t been delivered yet.” Along the way, the Army realized that there were other vehicles for which it needed simulators, so first the Leopard 2 and, in 2015, the new TAPV were added.

Price, too, played a role. Looking at an estimated cost of $400 million, the Army spent some time investigating the options for a public-private partnership as a way of developing the system more cheaply. It ultimately opted for a competitive approach. The project should enter the definition phase by June of this year. The Army knows what it wants, the next phase is how to get it. The goal is to have one site active by 2024 and all five in place by 2027. At present, the plan is to have the facilities run by civilian contractors.

“We want the Army to be able to go in and train,” said Ramacieri, and leave running the sites to someone else. When it is all in place, the Army will have a world-class training system, the equal of any other army’s.

Ultimately, it may even be possible to link the five sites so that soldiers in different parts of Canada could train together in the same virtual environments.

More, the system will actually save money in the long run. Working with the assumption that half of all driver and gunnery training and on the order of 20 percent of all crew training will take place on simulators in future, the Army expects to save up to $140 million in fuel and ammunition and in wear and tear on its vehicles over the 30-year life of the project.

One of the features planned for the new system will be perfect recreations in virtual forms of all the bases where the sites are located. Virtual copies of reality – that is getting close to The Matrix. But one intended to augment reality, not ultimately replace it. “Simulation will always be the gateway to live training,” said Ramacieri.