By Steven Fouchard, Army Public Affairs

Lieutenant-Colonel (Retired) Stéphane Grenier says he would never have written a book about his experiences with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) if not for the urging of friends and acquaintances.

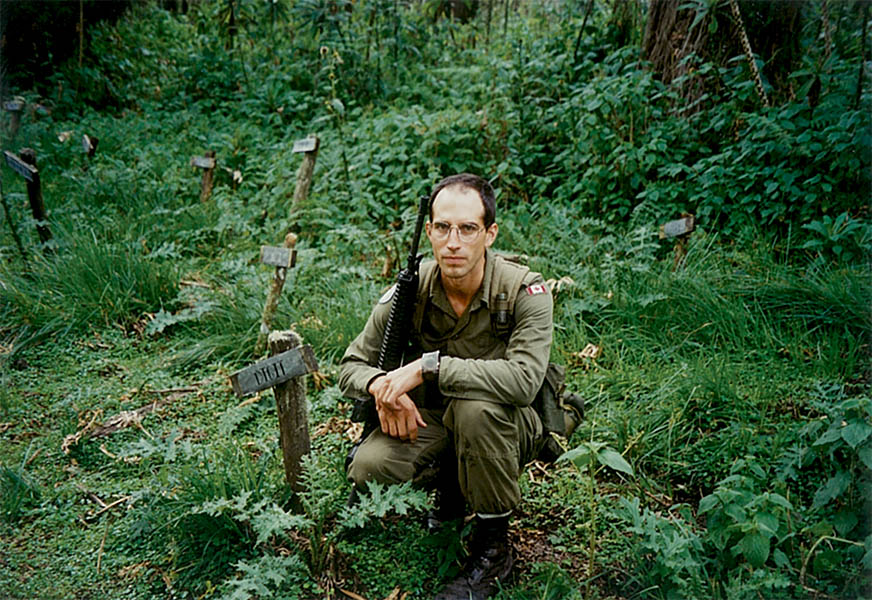

He may not think of himself as a writer but his story, revealed in After the War: Surviving PTSD and Changing Mental Health Culture, his newly-published memoir (co-written with Adam Montgomery), is very much about words. LCol (Retd) Grenier came home in 1995 from a 10-month deployment to Rwanda, site of a horrifying genocide, deeply traumatized.

He also faced a Department of National Defence (DND) ill-equipped to help those suffering – one that used the loaded term “disorder” to describe the invisible, mental injuries of war. The military, he also says, may have been speaking “about” such things but rarely spoke “to” the injured.

In parallel with his own recovery, LCol (Retd) Grenier pushed for reform at DND and had a profound impact. Among many other things, he coined a term, “Operational Stress Injury” that removed some of the stigma attached to mental illness in the military and continues to influence thinking at DND today.

Since his retirement in 2012, LCol (Retd) Grenier has continued in his efforts and expanded them into the private sector as a consultant. In the following interview, he discusses how peer support complements clinical care, the importance of helping both the injured and their family members, and the deeply personal investment he has in his current mission.

What made you decide to write After the War?

I never really wanted to write a book, but over the course of the last decade, people have suggested I should. One day, I was asked to speak and bring 75 copies of my book for a signing after the event and I said, “Well, I don’t have a book.” Over the years, the question kept coming back and I decided, “I’ll just follow that advice.”

Was there something in particular that made now seem like the right time for your story?

I left the military in 2012 and became a consultant. My company, Mental Health Innovations (MHI), started growing and I noticed corporate Canada really needs an infusion of innovation when it comes to mental health in the workplace. So the book, really, is not about Rwanda. The book is about what Canadians – the mental health system, corporate leaders – need to think about to better support their people.

It’s one thing to work with an organization of 6000 employees and make a difference there but I thought, “wouldn’t it be cool if we could get governments to think differently?” So I think the book is relevant to that objective.

You say in the book that simply talking with a colleague at National Defence was ‘the first domino to fall’ for you on the road to recovery.

It’s so simple, right? Having a colleague in the workplace who notices you’re not well and instead of looking away leans in and offers you non-judgmental support. But our economy, whether it’s the military or corporate Canada, is a competitive space and we’ve forgotten that people are the most important asset. People are too busy to notice that other people aren’t doing well and they really don’t think having a human-to-human conversation is part of the solution.

And the military especially is a very judgmental subculture. Infanteers will judge clerks, for example; ‘He or she doesn’t do what I do so therefore they don’t have any reasons to complain.’ The infanteers don’t know that the admin clerk who served in Afghanistan saw things driving in a convoy every week to resupply a forward operating base and that, in fact, it’s even worse for them because they’re not fully trained for it. That’s a barrier to authentic conversations because we feel judged, we don’t want to be judged, and so we just suck it up. So what do we do? We refer people to doctors and that’s all we know to do. We forget that sometimes just a conversation can be huge in people’s lives.

Balance is a key theme of the book. You talk about the divide between those who mistrust the medical system and a medical system that distrusts peer support because it is not based on formal education. You say the solution lies somewhere in between.

I think the mental health system needs to be humbled to some degree because we have created one in Canada that is very prescriptive. It’s anchored on the medical perspective. There’s nothing wrong with the medical perspective and I need to make sure I’m not portrayed as being against it. The difference between healing the brain and healing other parts of the human anatomy is that the person must be empowered to believe they can heal and recover. It’s not only therapy and medication that are needed to support that.

Introducing the notion that laypeople – in other words peer supporters – are part of the solution, is sort of a humbling experience for mental health clinicians. With the arrival of Peer Support Canada, which is an organization I founded after my work with the Mental Health Commission of Canada, peer supporters have now been transferred over to the Canadian Mental Health Association, where accreditation services are provided for them.

Once Canada realizes there’s a way to grow peer support in an accountable, systematic way – the same way it does for many other professions in this country – health care systems will really be able to transform themselves.

Your ex-wife Julie describes your post-Rwanda struggles from her point of view in the book. How did you feel reading that for the first time?

I was sad. I always sort of knew her perspective – we had talked about it – but it really made me sad. And the message is it’s so important for all organizations, the military and beyond, to not only support employees who are going through these struggles, but to support the families in better ways. They will reap the benefits of that because, if you support the family, you support your employee at the same time. It is all connected.

What’s your view of how far the Canadian Armed Forces has come on these issues?

I think you guys are continuing to grow at your own pace and continuing to improve things. What I realized when I left is, despite the challenges the military has, and despite the criticism it and Veterans Affairs are up against on a regular basis, our military people and our veterans are much better served than the average Canadian citizen. My two years at the Mental Health Commission of Canada made me realize how difficult it is for Canadians to recover from these situations.

So I have dedicated my full attention now to serving Canada in a different way, trying to make it better for others who don’t serve their country directly but who deserve as much support from the mental health system as the military. And as a Canadian taxpayer, I want to make sure that if my granddaughter, God forbid, ever develops a mental health problem, we’ve created a better system.