by Chris Thatcher

If the Army had callsigns for projects and initiatives, instead of the ubiquitous acronyms, the effort to develop a cloud-based tactical network might have been dubbed Roadrunner. In less than 12 months, Cloud TAK has gone from an idea to a deployable capability, moving the Army closer to parity with core allies who have already embraced and adopted cloud technology.

In May, the Directorate of Digital and Army Combat Systems Integration (DDACSI) cleared the way for Cloud TAK on domestic operations, a first step to being deployed on international missions.

Just under a year and a half ago, the directorate was proving the concept of a cloud-based tactical network on Exercise Maple Resolve. Equipped with Tactical Assault Kit (TAK)-enabled tablets and UHF radios, the opposition force was able to employ an ad hoc network at the tactical edge to frustrate the primary training audience.

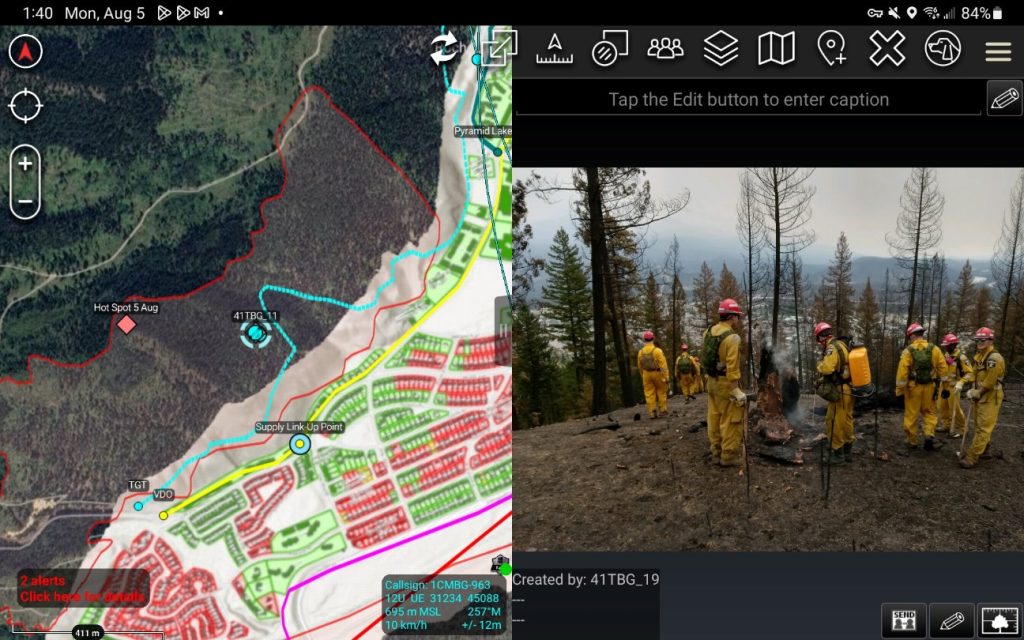

As the two-week exercise concluded, and forest fires ignited across Quebec, DDACSI saw an opportunity to continue testing and evaluation of the capability on Operation Lentus, rapidly equipping Regular and Reserve members of the 2nd Canadian Division with the civilian application of TAK (Team Awareness Kit), to allow military and provincial agencies to access a common map, share information, and conduct text chats from their personal cell phones, as they collectively battled the blaze.

“The forest fire in Quebec was pretty much a proof of concept,” said Major Martin Simard, who has spearheaded the initiative for DDACSI.

Since the fall of 2023, Simard has gathered the lessons of Maple Resolve and Op Lentus, refined an operational framework with Amazon Web Services (AWS), received approval from the Army commander, and drafted a fielding implementation order to help the Army field Cloud TAK.

Seeking to avoid some of the pitfalls that have hampered the Land Command Support System, he endeavoured to “design something robust that the whole Army can use and can scale.” Importantly, for a Royal Canadian Corps of Signals that is among the Army’s leading “stress trades,” functioning at just above 60 percent of its ideal strength, it had to be simple to deploy and maintain.

The networking capability deployed on Maple Resolve and Op Lentus was cobbled together leveraging several existing relationships with suppliers such as Base Camp Connect, Inter-Op, Rheinmetall, L3Harris and NORTAC Defence. Its underlying strength, though, was the cloud services provided by AWS, which offered computing and data storage as well as a paradigm shift in capability development—rapid solution development and deployment in days rather than months, fundamentally transforming how the Army conceptualizes and implements digital capabilities.

Simard has continued to lean on many of the same suppliers and has worked with AWS engineers to ensure the system keeps evolving even as it is being further developed. And because it is cloud-based, security patches and other updates are automatic. “By bringing our workload onto the cloud, we can make changes available to everyone, instantly. This agility allows us to deploy new features or capabilities in days or weeks instead of months or years,” he said.

This summer, DDACSI began distributing about 500 tablets and 700 cellphones with CivTAK, a version of the WinTAK software widely adopted by first responder agencies in the United States, to Regular, Reserve and Canadian Ranger units across the country. The units were identified in part for their likelihood of being tasked to support provincial governments combatting forest fires and other natural disasters.

“The intent with all those devices was to give a minimum viable capability to be able to connect to Cloud TAK, to be able to respond to domestic operations,” Simard explained. “They were sent to each Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group, each Reserve Canadian Brigade Group, as well as some of the Rangers.”

“The sales pitch I have for Cloud TAK is that we are connecting the Regular Force, the Reserve Force and the Rangers into a single battle management application. Everyone can connect to Cloud TAK, and if they need to, they can all speak together.”

By adopting a cloud-based approach, DDACSI has removed the procurement of servers and other expensive components that might have taken years to acquire, and shifted the focus to edge devices, software, and, for domestic operations, access to LTE or satellite networks.

“Wherever you have LTE coverage, you can connect a tablet or cellphone to the cloud,” he said. “At the moment, Cloud TAK is mainly for domestic operations, individual training, and collective training in Canada. We did prepare to support Haiti, [but] that was an exception at this point.”

While the immediate focus is perfecting the system for domestic operations, deployment for humanitarian responses and eventually international missions could follow quickly. Simard suggested that by the time members of 1 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group (1 CMBG) in Edmonton begin preparing for their next rotation in Latvia, Cloud TAK could be approved and ready to go.

“The intent is to connect them to the cloud,” he said. “1 CMBG is really exploiting the success of Cloud TAK. It’s been great for me to see because, I’ve been working on this largely by myself for a long time. So, to see others understand the capability is rewarding. Even though all the documentation is not yet ready, I know Cloud TAK is in good hands, because right now they are the furthest advanced with Cloud TAK within the Army.”

Assuring users and commanders the cloud is secure will be a critical step. Simard has worked with AWS and National Defence personnel to ensure compliance with military-grade security standards, and addressed concerns about data sovereignty and data confidentiality, integrity and availability. Though the cloud would be globally accessible, the data is held in Canada, at AWS’s Canada-Central-1 Region in Montreal.

Simard noted that the wider adoption of cloud technologies might also resolve data security related concerns. At the tactical level, NORAD began deploying secure cloud-based command and control (CBC2) to its air defence sectors last year and is now looking at how to scale that for the operational layer, such as air operations centres.

“Within Canada, the Royal Canadian Air Force is leading this to be able to look at secret cloud and what we need,” he said. “The Army is leading Cloud TAK, and the RCAF will be leveraging it. The intent is, whenever the RCAF is able to leverage partner environments for operational effect, we will follow – we will reuse their work.”

The flexibility of cloud-based networking offers its own form of security, Simard added. “You can see it with Ukraine. As soon as the war started, they migrated all their work into the cloud. It allowed them to keep the government running. I believe the cloud is a great solution, but we need to maintain services at the edge, and we always need to be able to work in a denied environment where we lose the connectivity to the cloud.”

Because the hardware of tablets and the software of TAK are already intuitive for many soldiers, training users should be relatively straightforward. Simard has already created a video to explain Cloud Tak, and is now working on a training video specific to soldiers.

“The way Cloud TAK is designed, it is just like using Google Maps, except that it is protected by a VPN. I just turn on my tablet, open VPN, turn on TAK, and I am connected. Also, we are leveraging the credential that we have within Office 365. In the past, for an exercise, the local administrators had 50 sheets of paper with usernames they had to manually enter. Now, everything is automated.

“The biggest delta for the training is really for the Information System Technicians within the Army, because cloud is new for them. But once they are connected, they don’t have to architect anything, they just have to use it, and the tools that they used to use on their bare metal system are the same tools that they use on the cloud, it’s just a different way to access them. As long as we’re not asking them to build a system, we’re good to go.”

If the Army requires staff to build additional applications, “we’re not there, and that’s what will take time,” he said. “That’s where we need to leverage industry to help us. Because that’s going to be a big gap to cover for the training institution.”

By initially introducing Cloud TAK on domestic operations, Simard believes that Army can buy some time to focus on techniques, tactics and procedures, and “how to train our technical people properly.”

Switching to a cloud mindset and how to fully exploit the capability takes time, he acknowledged, but the Army needs to embrace it because allies like the U.S. Army are heavily invested. “They are already deployed on cloud. The agility you get from being on the cloud is incredible, and when people realize it, it is a force multiplier.”

In the near term, Simard has a more entrepreneurial vision for Cloud TAK: To share the Canadian Army’s success with cloud-based command-and-control with other agencies involved in domestic response. Because the current architecture is essentially code, with no controlled goods and no military information, he believes it could be packaged into a basic service for other government agencies and provincial and municipal first responders to connect and share vital data in times of crisis.

“It is pretty much a command-and-control solution out of the box,” he said. “You will know that whenever you deploy onto domestic operations with the Army, or with other agencies, that you will be able to communicate.”