by Michael Rostek, Nancy Teeple, Yazan Qasrawi

State militaries routinely engage in forward planning for a variety of reasons ranging from defence procurement to the assessment of emerging forms of warfare. Uncertainty, however, is a predominant characteristic of the global future security environment, and defence establishments strive to understand how their national security policies will fit in this emerging paradigm.

The complexity and uncertainty of today’s global environment has created a bewildering array of interactions and interdependencies requiring leaders to systematically assess their environment to reduce surprises, increase flexibility, and improve manoeuvre. Planners, however, typically seek to diminish uncertainty rather than account for it. Such an approach is risky.

Yet, if the future is uncertain, then how do military planners prepare for it? Structured methods for exploring the future allow for investigation of the future and its implications in a manner that is systematic and rigorous. Moreover, the results obtained using such methods are likely to be more credible and useful than any that might be obtained in their absence.

One of these structured methods is strategic foresight – an approach that enhances decision making through the development and sustainment of a systematic long-term forward view to planning and application of emergent insights in an organizationally useful way.

Organizations today, whatever their form, are increasingly turning to strategic foresight to better understand the complex and rapidly changing environment within which they must operate. Strategic foresight is a growing international discipline designed to critically examine, address, and minimize the difficulties of making long-term decisions under uncertainty.

Strategic foresight can be directed to large- or small-scale issues, in the near or distant future, to project possible or desired conditions. It helps to provide a framework to better understand the present and expand mental horizons. From shaping strategy to guiding policy or detecting adverse conditions, employing a strategic foresight approach changes the way planners think by broadening their perspectives about the external environment in which they must operate in the future by embracing uncertainty and emphasizing adaptability and action.

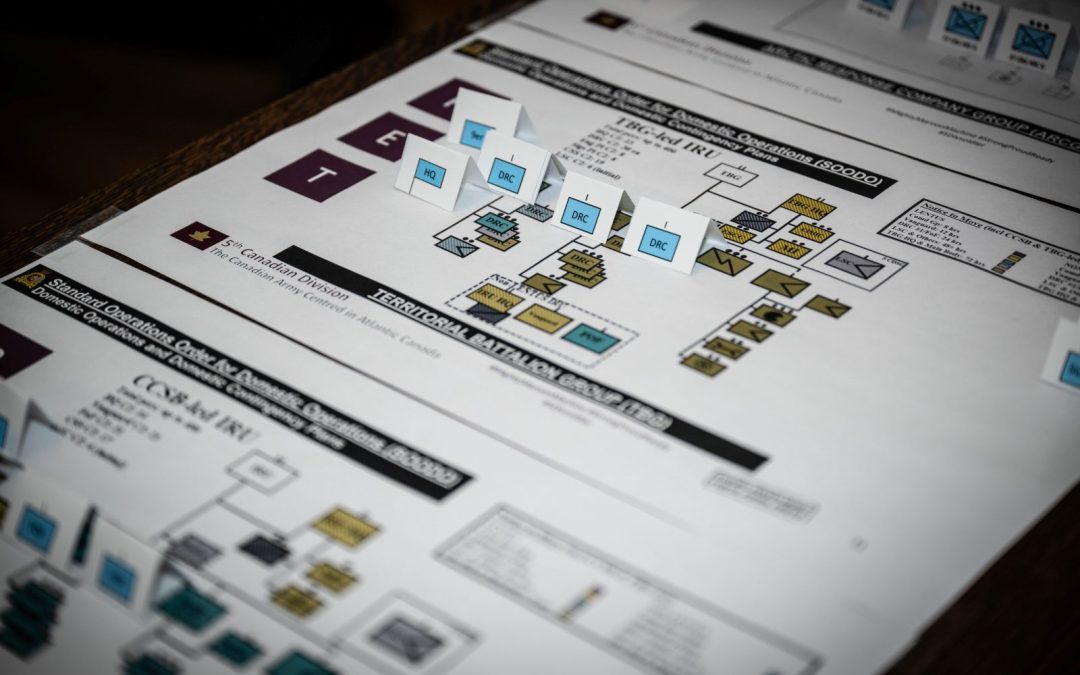

Photo: Cpl Genevieve Lapointe

There are a wide variety of tools available to support a strategic foresight approach, the most common being environmental scanning and scenarios.

Strategic foresight includes the analysis of key dimensions of the international environment, how conditions may change due to major trends and drivers at work in the international system, and the implications of such changes for implementation of policies and actions, and the consequences of these policies and actions. Commonly analyzed dimensions of the international environment include society, technology, environment, economy, and politics, referred to as the STEEP framework.

A key strategic foresight tool is environmental scanning. Environmental scanning across the STEEP categories is a process involving the acquisition and use of information about events, trends, and relationships that may have a strategic bearing on how an organization does business. The knowledge and insights gained from scanning serve to assist in more effectively planning an organization’s future course.

The process typically focuses on multiple areas, in effect covering every major sector of the environment that can assist in planning for an organization’s future. It involves four basic techniques that are essential to the method’s effective use: undirected viewing, which helps the organization to scan broadly and develop peripheral vision to see and think outside the box; conditioned viewing, which tracks trends and provides early warning about emerging issues; informal search, which constructs a profile of an issue or development, allowing the organization to identify its main features and assess its potential impact; and formal search, which gathers all relevant information from primary and secondary sources of information about an issue to enable intelligent decision making.

When environmental scanning is applied to the future security environment, it produces usable analysis of the future security and operating environments with implications for planning. The environmental scanning outcomes (e.g., trends, drivers) are subjected to a range of analytical tools (e.g., impact-uncertainty analysis, future wheels, cross impact analysis) to provide deeper understanding and meaning of the scanning outcomes.

Uncertainties about the future are both numerous and unknown but remain vitally important to the strategic foresight approach as they identify the most important aspect of the alternative futures.

Results are then typically presented as the baseline future (i.e., the expected future based on trajectories of current and emerging trends) and alternative futures (i.e., unexpected and controversial futures resulting from change in trends impacting anticipated trajectory). An alternative future is a logical, coherent, detailed, and internally consistent description of a plausible future operating environment. Alternative futures provide a means to envision a range of possible future requirements and hedge against uncertainty.

It is tempting to focus on the outcomes considered best or most likely, but even the best-laid plans can go wrong. It is therefore better to examine a broad range of possibilities and the forces driving them, to understand the dynamics of change to identify initiatives that may do well under a range of different circumstances.

Members of 5th Canadian Division’s G3 operation cell during a wargame in December 2023 to assess the operational impacts of the upcoming commitment to Task Force Latvia. Photo: MCpl Stephanie Labossiere

The next step in the process is to create scenarios, which tell a story built around the components of the alternative futures. Writing the scenarios is a challenge and archetypes can be used to aid in this process. Archetypes provide the generalized framework or structure for developing the scenario stories, for example: “Continuation” – the system continues along its current trajectory; “Collapse” – the system breaks or falls into a state of dysfunction; “New Equilibrium” – the system is confronted with a significant challenge and adapts; and “Transformation” – fundamental changes to the system emerge. The archetypes provide the ingredients or plot elements which are applied to the alternative futures to create a useful scenario story.

Scenarios are carefully constructed snapshots of the future and the possible ways that a sector might develop. Scenarios help focus thinking on the most important factors driving change in any field. The goal of using scenarios is to reveal the dynamics of change and use these insights to reach sustainable solutions to the challenges at hand. Scenarios do not predict the future. Rather, they are tools to help explore the different ways the future might unfold to form a shared vision, develop strategies, and create high-impact policies to be implemented now. Most importantly, scenarios improve understanding of the mechanisms underlying change, thus they strengthen strategic planning.

A scenario for a given field ought to tell what each of the major stakeholders could expect in a certain set of circumstances, so decision makers at all levels should find scenarios useful. A well-constructed scenario must contain enough detail to be useful for strategic planning, but not so much as to become overly specific and irrelevant to the issues of interest. Scenario developers must be inventive and imaginative, without letting their stories become too obscure or fanciful.

It should be emphasized that scenarios are not the end state of a strategic foresight approach and further analysis must be undertaken to make the scenarios useful for strategic planning.

The analysis of scenarios begins with an evaluation of the scenarios or what is more commonly referred to in military environments as wargaming. This evaluation is typically built around two criteria: how likely is the scenario, and how unprepared are you for the scenario. The aim of this evaluation is to discover whether any of the scenarios are especially important or unimportant and this helps to recognize previously undiscovered issues or priorities.

This evaluation then informs the next step which is implication analysis. The implications analysis transitions the analysis of the external world to the internal planning of the organization. Alternatively, the scenarios describe the wider impact of the environment whereas the implication analysis explores the changes implied for the planners. During this analysis, each of the scenarios are rigorously analysed through a typical process outlined as follows:

- Decide of the level of analysis to be analysed: global, industry or organization;

- Choose the categories (e.g., energy security) you wish to focus on as derived from your scenario;

- Identify the challenges in each identified category;

- Identify 1st, 2nd and 3rd order impacts or consequences for each challenge;

- Prioritize significant or provocative implications; and

- Identify themes, opportunities, policies, or strategic issues to address.

Upon completion of this analysis, the planners are then ready to address planning options and provide guidance to decision makers. Here the planner uses the analysis to advise on issues to avoid, identify what is most likely to take place, and what to work towards. Further, planning recommendations are made more robust by developing contingency plans to deal with the unexpected.

The ultimate aim of adopting a strategic foresight approach is to make better informed decisions today. Strategic foresight must link to an organization’s mission and effectiveness. The payoff for taking action on planning that has utilized a strategic foresight approach is often not immediately seen. Therefore, acting on the results of this work is typically about communication, establishing buy-in, and then translating the plans into concrete action.

Strategic foresight informs the conceive pillar of the capability development continuum, setting the stage for designing and building Canadian Army capabilities. In addition, this approach engenders a team decision making capability that facilitates non-linear thinking, thereby enabling innovative approaches to today’s emerging threats. Strategic foresight continues to be a component of the Canadian Army’s capability development toolbox at the Canadian Army Land Warfare Centre.

It should be well-understood that it is not a panacea, but rather it provides a logical methodology to anticipate change in a turbulent and uncertain world. It helps increase a decision maker’s ability to be flexible and adaptive to changing possibilities and circumstances. Those who have participated in strategic foresight projects often claim that the real strength of the foresight approach rests in an increased capability within a planning team to deal with strategic surprise or unforeseen shocks.

There are also those who argue that strategic foresight should be considered a duty for all organizations to enhance readiness in an era of rapid and relentless change. Military planners win when the effects of surprise do not inflict lethal loss of blood and treasure.

Dr. Michael Rostek is with the Defence Research and Development Canada’(DRDC) Toronto Research Centre, and Dr. Nancy Teeple and Dr. Yazan Qasrawi are with DRDC’s Centre for Operational Research and Analysis (CORA).